Science Series #14: Leishmaniasis

What is leishmaniasis?

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease (NTD) that is spread through sand flies in tropical and subtropical areas around the world. These flies carry the Leishmania parasite, causing various subtypes of this disease to appear in different patients. The three main forms of the disease that have been identified by the World Health Organization (WHO), along with their subdivisions, include visceral leishmaniasis, which is the most serious, cutaneous leishmaniasis, being the most common, and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis.

(Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization)

Types of leishmaniasis

Visceral leishmaniasis, the most severe form of the illness, affects major internal organs such as the spleen, liver, or bone marrow, which can lead to serious health complications. While it is possible to have a silent infection of visceral leishmaniasis, patients usually experience high fevers, weight loss, abnormal blood test levels, and swelling of the spleen and liver. There are currently an estimated 100,000 cases globally per year.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis, the most common form of the illness, tends to cause skin sores along the patient’s body. The sores tend to appear as bumps or lumps, with the possibility of evolving into ulcers that can lead to scabbing on the skin. For this type of leishmaniasis, it is possible for patients to show no symptoms or signs of having been infected with the parasite, but they can still be vectors in the transmission cycle. Humans are not always needed to keep the cycle alive since there are many cases where other mammals, such as rodents or dogs, can help continue the cycle. However, anthroponotic transmission, which is the transmission from humans to flies to other humans, can still be possible and can be found in different areas around the world. It is estimated that the number of new cases globally per year are between 700,000 to 1.2 million.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis can lead to partial or full destruction of various mucous membranes, including those in the nose, mouth, and throat. The epidemiology of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in the Americas region is complex, with variations in transmission cycles, hosts, vectors, clinical manifestations, and response to treatment, due to the presence of multiple Leishmania species in the same geographic region.

(Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization)

Localization of leishmaniasis outbreaks

Leishmaniasis tends to affect people in tropical and subtropical areas, where Leishmania can be found in flies that carry it from human to human. Leishmaniasis can be found in different parts of Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Southern Europe, along with Central and South America. With this information, it is believed that leishmaniasis can be found in around 90 countries worldwide. However, in some countries, cases of leishmaniasis appear due to globalization (tourism, business trips, etc.), which brings the parasite to areas that previously did not have it. The tropical and subtropical climates of these countries are important to focus on in regards to observing this disease through an epidemiological lens. It is known that leishmaniasis is more common in rural areas, though it can also be found in the outskirts of cities.

(Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Negative factors

Climate is an important factor in determining the geographical range in which the flies can spread the parasite. Hotter climates in areas such as rainforests or deserts tend to increase the spread of the illness, while colder climates manage to stall the spread. Leishmaniasis has also been linked with climate change and its causes, such as deforestation and urbanization. As previously mentioned, leishmaniasis is usually found in rural regions. These rural areas also tend to have a lower socioeconomic demographic, which negatively impacts the distribution of diseases in the community. This disease tends to affect the poorest people and has been associated with malnutrition, homelessness, and a lack of resources. All of this points to leishmaniasis mainly affecting disenfranchised communities with a low number of resources.

(Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization)

Available treatments

Leishmaniasis can be spread to any individual of any age, which is why having treatments available is critical for helping many disenfranchised communities. There are multiple treatments available that have been established to help with recovery. When looking at treatments, it is important to identify which type of leishmaniasis is present in the individual along with the severity of the case. While the skin sores caused by cutaneous leishmaniasis tend to heal on their own, it can even take years, and treatment can help them heal faster without leaving as many scars.

There are drug regimens that have been developed to treat the disease and are administered to each patient based on physicians’ orders. Mainly, the treatment depends on several factors including type of disease, concomitant pathologies, parasite species and geographic location. Therefore, treatment decisions should be individualized. It must be noted that treatment tends to be long, more than one course might have to be given, and there is a chance of the infection relapsing. Even after a round of treatment, patients must be observed for up to a year after to ensure no remission has occurred before they can be pronounced cured of leishmaniasis.

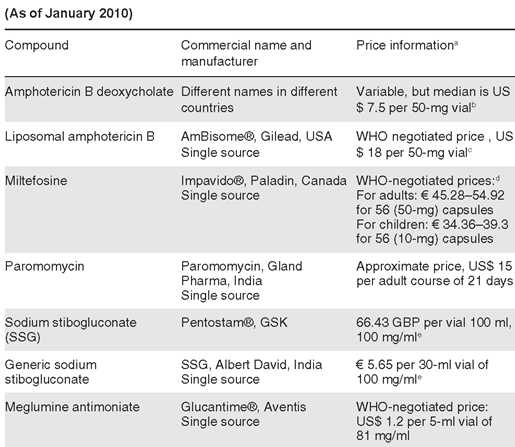

The most commonly used drugs in the treatment of cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis are pentavalent antimonials, in two different formulations: antimonate N-methylglucamine and sodium stibogluconate. Drugs such as pentamidine isethionate, miltefosine, amphotericin B and liposomal amphotericin B are other therapeutic options. As of March 2014, the FDA has approved miltefosine to treat all three types of leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral. When miltefosine was given daily over the course of 4 weeks, 94% of patients were cured, and the drug was seen to be reasonably safe. However, this drug has drawbacks. The first is that the drug must be taken under a regimented schedule. If patients do not adhere to the directions of the drug, the parasite has a chance of becoming drug-resistant which, with anthroponotic transmission, can spread the treatment-resistant parasite to other individuals. The second drawback is that pregnant women cannot take this drug and pregnancy must be avoided for at least two months after the regimen is completed.

In the case of cutaneous leishmaniasis, the sores that are caused by the parasite will not be healed by miltefosine. The sores can heal on their own with time, but this could take longer and comes with a higher probability of developing scars. Treatments for dealing with the sores can be as simple as applying cold or heat to the areas with lesions in order to kill the parasites present. Applying an antibiotic ointment known as paromomycin directly to the sores could also help.

Unfortunately, and although there are some drugs available, no single drug completely eliminates the parasite. Treatment includes disease management of the patient, the reduction of the parasite’s burden on the body and the resolution of skin or mucosal lesions by the monitored use of the appropriate medicines. The severity of adverse effects associated with systemic treatment has led to the acceptance of local treatment (intralesional administration of or thermotherapy) for localized cutaneous leishmaniasis.

(Sources: World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Organization for Rare Disorders, and Therapeutics and clinical risk management)

Specialized treatment cases

In the case of cutaneous leishmaniasis, since it is not a life-threatening condition, the recommended drug or treatment approach should not induce life-threatening complications. Hence, the treatment decision is based first on the risk–benefit ratio of the intervention for each

patient. Different treatment options become available if any one of three situations occurs with the patient in question: cutaneous leishmaniasis develops into mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, the patient has a weakened immune system, or that the patient has larger skin lesions than average. If any of these conditions are met, then treatments such as liposomal amphotericin B, miltefosine or sodium stibogluconate can be prescribed. These treatments, however, have only been approved for visceral leishmaniasis by the FDA, and while they have been used to attempt treatment of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, there are no established treatments for those types of disease. Through all this, it is important to note that the best way to battle this disease is by preventing it from spreading. This can come about by finding new ways to stop the cycle of transmission, such as preventing the spread through fly bites or making sure there are limited contaminated vectors that can help spread the disease.

(Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Organization for Rare Disorders)

Developing leishmaniasis treatments

There is limited information on up-and-coming treatments for leishmaniasis. Whether it is because this illness tends to target those in poorer communities or due to other illnesses taking precedence due to higher incidence rates, it is still important to focus on ways to help the people getting affected by leishmaniasis. It is known that researchers are working on creating different vaccines to prevent or lower the chances of being infected with leishmaniasis. These vaccines could activate the immune system to kill the Leishmania parasite that is introduced in individuals before the parasite can establish itself and begin causing sores or worsening the patient’s condition.

(Source: National Organization for Rare Disorders)

JCWO´s background in leishmaniasis

In 1948 Dr. Jacinto Convit began studies in leishmaniasis; with the initial experience in leprosy. Dr. Convit and his team described the similarities between these two diseases according to the clinical, immunological and pathological aspects. Years later, after the success of the leprosy therapeutic vaccine, in 1986, Dr. Convit used the same model to develop a vaccine to treat leishmaniasis. When treating patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis, pasteurized Leishmania promastigotes were used in combination with bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), observing regression of the lesion and local disappearance of the parasites. This treatment was applied in several countries such as India, Iran, Colombia, Norway, among others; and were recognized by the WHO as potential treatment for this disease. In 2010, the WHO recognized Dr. Convit’s treatment for leishmaniasis, as part of the first generation of vaccines against this condition.

(Source: Convit et al., 1986, 1987)

(Source: World Health Organization)

Works Cited

“CDC – Leishmaniasis.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 14 Feb. 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/index.html#:~:text=Leishmaniasis%20is%20a%20parasitic%20disease,bite%20of%20phlebotomine%20sand%20flies

“Leishmaniasis.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 8 Jan. 2022, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

“Leishmaniasis – NORD” NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders), 28 Aug. 2019, https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/leishmaniasis/

Sundar, Shyam, and Piero L Olliaro. “Miltefosine in the treatment of leishmaniasis: Clinical evidence for informed clinical risk management.” Therapeutics and clinical risk management vol. 3,5 (2007): 733-40.

World Health Organization. “Control of the Leishmaniases”. WHO Technical Report Series 949 Report of a meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniases, Geneva, 22–26 March 2010.